It is not uncommon for states to engage in conflicting behaviors regarding human rights issues in domestic and foreign affairs. When a state’s domestic human rights abuse receives international criticism, the escape approach taken by the criticized state is to claim that it’s a matter of state sovereignty. As a result, we often see the rekindling of the debate on the indivisibility of international human rights regimes and state sovereignty. And the situation of human rights abuse in Xinjiang is a classic case of this scenario. It cannot be denied that powerful states employ double standards in interpreting international human rights norms according to their own interests, but so do non-powerful states such as Brunei, Kazakhstan, Myanmar, and Uganda. However, this article focuses on China’s double standard in its international stance on human rights and its domestic human rights abuse in Xinjiang to emphasize the transition that the international community has to endure with growing China’s clout in international institutions. Unlike less powerful states, China’s (re) interpretation of international human rights norms and its attempts towards alteration will have a broad impact on the universality of international human rights norms.

China’s remarkable economic expansion has amplified its diplomatic reach and has ramped up choreographed efforts to infiltrate United Nations (UN) human rights bodies. China has questioned the concept of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), seeing it as a Western invention. It has garnered attention and support from like-minded states at the international human rights regime by invoking the concept of cultural relativism[1]. Of course, state sovereignty is the principal element of the international system, however, states also have rights and duties under international law to limit the potential abuse of power.

However, among authoritarian nations like China, the popularity of cultural relativism, a concept that denies the existence of universal law/norms and promotes tolerance for different cultures of state(s), underpins the widespread political benefits. China’s interpretation of human rights is incompatible with the concept of universality. Its conception of human rights is based on rights to subsistence and growth, whereas civil and political rights are ignored[2]. This suggests that the universality of human rights is under threat because it serves as a deterrent to relativism. A state uses a relativist argument to deflect criticism of domestic human rights violations and try to get away with it by framing it as a threat to sovereignty. Xinjiang is facing the fate of cultural relativism where the Uyghurs and other Turkic groups are subjected to the worst forms of human rights abuse under the banner of state sovereignty. China’s record of human rights violations is not a new phenomenon. It has a history of Communist dictatorship surviving by repressing people, human rights advocates, lawyers, media personnel, scholars, social activists, ethnic minorities, and students with a zero-sum mentality toward freedom of expression and criticism. Under Xi Jinping’s governance perception about China has changed dramatically. China, an emerging power whose rise has been rapid and dramatic internationally and internally, depends too heavily on economic coercion, repression, retaliation, and wolf warrior diplomacy.

Repression:

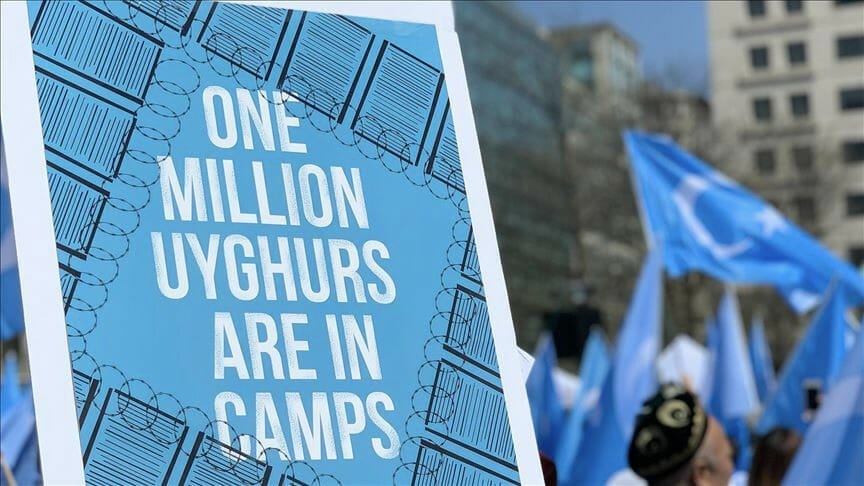

Xi Jinping’s intolerance of any criticism of the party-state has been the main source of human rights breaches. His strike-hard policy has been particularly harsh in dealing with the 13 million Uyghurs in Xinjiang who are subjected to arbitrary incarceration, torture, sexual misconduct, including rapes, and forced sterilization–due to which birth rates in Xinjiang among the Uyghur community has declined[3]. According to the Newslines Institute for Strategy and Policy, a forceful state-mandated labor transfer and poverty alleviation scheme forced hundreds of thousands of ethnic minority laborers in Xinjiang to pick cotton[4].

Because Chinese officials no longer refer to China as a multiethnic country, ethnic policies have evolved radically towards making China a monoculture society. However, the Chinese party-state’s objective of building a cohesive national identity has been thwarted by the existence of the Pan-Islamic or Pan-Turkic identities, resulting in widespread discrimination, repression, and limits on Uyghurs’ basic human rights. Adrian Zenz’s research in 2017 disclosed the construction of concentration camps in Xinjiang, which initially was denied by China but eventually, the state media–including the China Daily— started to refer to camps as centers of ‘vocational education and training centers’[5].

According to public testimonies from released and escaped detainees, there could be any basis for detention, including having family living abroad, traveling abroad for Haj Pilgrimage, studying abroad, practicing religion, participating in unauthorized religious activities, women wearing hijab/headscarves, keeping Muslim names, or sharing Islamic texts or Quranic verses. The Uyghurs who are outside of the detention centers are also not fortunate either. They face widespread surveillance by officials assigned to stay in their homes, tracking their activities, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and family separations[6]. Many Chinese tech giants such as Huawei, ByteDance, and iFlytek, assist the government in waging an unprecedented high-tech crackdown[7]. Chinese party-state officials in Xinjiang have collected a massive amount of personal information, ranging from personal individual traits to tangible goods they own, and have stored all of the data on the Integrated Joint Operation Platform (IJOP), which informs the authorities of each individual’s whereabouts[8].

Chinese party-state has a higher status than the Chinese constitution, because not only are detention camps contrary to Chinese law, but detainees are also charged with a crime without having access to legal representation. Physical torture and abuse in detention camps are unquestionably violations of international human rights law, and only a few organizations, such as Human Rights Watch (HRW), Amnesty International (AI), and Radio Free Asia (RFA), have been vocal in naming and shaming China’s draconian policies and demanding an independent investigation.

Double Standard diplomacy:

China has expanded its normative space in human rights diplomacy by signing a number of international treaties, actively participating in and contributing to the work of numerous human rights organizations, consistently donating to peacekeeping missions[9], and sitting on influential boards like the Human Rights Council (HRC)[10]. It has since the 1990s issued White Papers (WP) on human rights celebrating its human rights achievements, while post-2014 a flood of WP was released focusing on progress and human rights development in Xinjiang. However, the two core instruments of the UDHR–the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which China has signed but not ratified, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which, despite its ratification, contradicts China’s actions in Xinjiang by overriding the Uyghurs’ cultural and social rights. Because of its active assistance in vetoing or stopping the high commissioner for human rights from speaking out against human rights violations, China’s advocacy has gained widespread backing from like-minded states. For example, China has blocked human rights abuse actions against Syria (2018)[11], has rejected a resolution calling for an open free election in Venezuela (2019)[12], has opposed resolutions against North Korea (2020)[13], and so on. China is attempting to establish an authoritative trend in the international human rights framework by normalizing pogroms, systematic human rights abuses, and genocide, which is a reason for concern because it will limit the UN’s power to call for action on human rights crimes.

Because the global response to human rights violations is divided, China’s activism should serve as a wake-up call for transatlantic states. At the UN Human Rights Council’s 41st session in 2019, the world witnessed a deeper alliance between like-minded authoritarian states. Twenty-two Western states, on the other hand, signed a letter condemning human rights violations in Xinjiang. In response, fifty like-minded states signed a letter four days later complimenting China’s anti-terrorism operations in Xinjiang[14]. This raises red flags about international human rights systems operating effectively and countries being immune to criticism based on internal affairs and state sovereignty. Despite the risk of jeopardizing the international human rights regime’s credibility, key advanced states have requested independent access to Xinjiang so that experts and diplomats can assess the situation.

In June 2020, fifty UN special procedures, special rapporteurs, working groups, and other human rights experts delivered an intense report on China’s human rights record underscoring the Chinese government’s “collective repression” of religious and ethnic minorities in Xinjiang and Tibet[15]. A cross-regional group of 39 states delivered a blistering public censure of the Chinese government’s human rights violations in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Tibet in October 2020. Since then, we’ve seen a modest but steady movement in calling China out[16]. On March 22, 2021 the EU, UK, US and Canada enacted a range of coordinated sanctions, such as freezing assets and travel bans against Chinese officials and entities[17]. On September 14, 2021 the High Commission for UN Michelle Bachelet told the UNHRC ‘ I regret that I am not able to report progress on efforts to seek meaningful access to the XUAR (Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region) but the office is finalizing its assessment of the available information on allegations of serious human rights violations’[18]. Recently The World Uyghur Congress (WUC) (an international organization of exiled Uyghur groups) from September 10-13, 2021 held a four-day Uyghur tribunal in London investigating China’s treatment towards the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The hearing had witnesses and experts testify about their experience in the crackdown. In December the tribunal will issue a final non-binding verdict on whether China is executing genocidal policies in Xinjiang, or crimes against humanity[19].

The case of Xinjiang is being contested around the world as to whether it is genocide or crimes against humanity; nonetheless, what can be claimed with clarity is that there is widespread evidence of human rights violations. Thus, impeding human rights abuse by (powerful or non-powerful) nations from becoming the new normal is a big and daunting problem for the international human rights regime.

Taiwan’s Response:

In Taiwan, the discussion of the Xinjiang concentration camps in the media and among political leaders is of the CCP’s heinous treatment of its population as a foreshadowing of what will happen if Taiwan is annexed by China. This is directly proportional to China’s double standard diplomacy and its intended one-country, two-systems framework. As a result, Taipei has taken steps and is continuing its efforts to raise awareness among Taiwanese citizens. In 2019 Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD) and the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT), and the International Religious Freedom (IRF) held a ceremony on ‘A Civil Society Dialogue on Securing Religious Freedom in the Indo-Pacific Region’[20] implying that human rights abuses in Xinjiang are a non-partisan concern for Taiwan. Early this year on April 23, an independent legislator, Freddy Lim (林昶佐), founded a Parliamentary group for Uyghurs to offer solidarity and support, as well as to protect human rights and liberal ideals[21]. And on July 30, 2021, the Taiwan Parliamentary Human Rights Commission held its first public hearing on Uyghur human rights violations in Xinjiang. In fact when a few Taiwanese celebrities joined the call with Beijing supporting a boycott of a clothing brand that expressed concern over forced labor on cotton plantations in Xinjiang, Premier Su Tseng-chang (蘇貞昌) urged Taiwanese citizens and celebrities to uphold human rights ideals[22]. Thus, given China’s interference in reducing Taiwan’s international recognition, it encounters challenges facing the China threat and formulating a cohesive policy on additional structural problems.

[1] Donnelly, Jack. 2007. “The Relative Universality of Human Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly, 29:2, 281-306.

[2] Angle, C. Stephen. 2002. “Engagement Despite Distinctiveness,” Human Rights and Chinese Thought A Cross-Cultural Inquiry, New York: Cambridge University Press, 214-250.

[3] According to reports by Adrian Zenz because of the birth control policies in Southern Xinjiang the population will be between 8.6- 10.5 million by 2040 contrary to the Chinese projection of 13.1 million. See, “Chinese birth-control policy could cut millions of Uyghur births, report finds,” BBC, 7 June 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-57383548 .

[4]Zenz, Adrian, “Coercive Labor in Xinjiang: Labor Transfer and the Mobilization of Ethnic Minorities to Pick Cotton,” Newslines Institute for Strategy and Policy, 14 December, 2020, https://newlinesinstitute.org/china/coercive-labor-in-xinjiang-labor-transfer-and-the-mobilization-of-ethnic-minorities-to-pick-cotton/ .

[5] “Has China set up concentration camps in Xinjiang?” China Daily, 27 August, 2020, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202008/27/WS5f470590a310675eafc55bf8.html

[6] “China: Visiting Officials Occupy Homes in Muslim Region,” Human Rights Watch, 13 May, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/05/13/china-visiting-officials-occupy-homes-muslim-region

[7] Cave, Danielle, Fergus Ryan and Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, “Mapping More of China’s Tech Giants: AI and Surveillance,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 28 November, 2019, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/mapping-more-chinas-tech-giants

[8] Dholakia, Nazish and Maya Wang, “Interview: China’s Big Brother App: Unprecedented View into Mass Surveillance of Xinjiang’s Muslims,” Human Rights Watch, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/05/01/interview-chinas-big-brother-app

[9] “China’s Role in UN Peacekeeping Missions ,” Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2018, https://isdp.eu/publication/chinas-role-un-peacekeeping/

[10] Sophie Richardson, “China Slanders and Smears at UN Human Rights Council,” Human Rights Watch, 11 March, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/11/chinas-slanders-and-smears-un-human-rights-council

[11] “Procedural Vote Blocks Holding of Security Council Meeting on Human Rights Situation in Syria, Briefing by High Commissioner,” United Nations, 19 March, 2018, https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/sc13255.doc.htm

[12] “Venezuela: US resolution vetoed by Russia, China at UN Security Council,” DW, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/venezuela-us-resolution-vetoed-by-russia-china-at-un-security-council/a-47734238

[13] “China denies weakening sanctions enforcement on North Korea,” Associated Press, 2 December, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/beijing-global-trade-north-korea-coronavirus-pandemic-china-9e53bf512fb345fab3b47c3133b125d9

[14] Yellinek, Roie and Elizabeth Chen, “The “22 vs. 50” Diplomatic Split Between the West and China Over Xinjiang and Human Rights,” The Jamestown Foundation, 13 December, 2019, https://jamestown.org/program/the-22-vs-50-diplomatic-split-between-the-west-and-china-over-xinjiang-and-human-rights/

[15] “UN experts call for decisive measures to protect fundamental freedoms in China,” UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 26 June, 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26006

[16] Statement by Ambassador Christoph Heusgen on behalf of 39 Countries in the Third Committee General Debate ,” Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the United Nations, 6 October, 2020, https://new-york-un.diplo.de/un-en/news-corner/201006-heusgen-china/2402648

[17] The individuals and entities are Zhu Hailun (former secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of the XUAR and former deputy head of the 13th People’s Congress of the XUAR); Wang Junzheng (Party secretary of the XPCC, deputy secretary of the party committee of China’s XUAR, political commissar of the XPCC); Chen Mingguo (Director of the XPSB since January 2021 and vice chairman of the XUAR people’s government); XPCC Public Security Bureau (in charge of implementing all policies of the XPCC relating to security matter, including the management of detention centers).

[18] U.N. rights chief regrets lack of access to Xinjiang’”, Reuters, 13 September, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/un-rights-chief-regrets-lack-access-xinjiang-2021-09-13/

[19] See, The Uyghur Tribunal, https://uyghurtribunal.com/

[20] http://www.tfd.org.tw/opencms/english/events/data/Event0758.html

[21]Wu Su-wei, ‘Freddy Lim establishes Uighur support group’ Taipei Times, 24 April, 2021. https://taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2021/04/24/2003756252

[22] Chen Yun and Jonathan China, ‘Premier Urges Public to take stand on human rights’, Taipei Times, 27 March, 2021, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2021/03/27/2003754575